This text gives an overview of traditional bow types, with data on their performance. Modern bows using modern materials and compound construction are briefly mentioned, but not taken into account any further. Sporting, hunting and war bows are all listed, though the modern recreative archer will find most of them rather heavy.

Handbows

The first bows were "shortbows".

There were held in front of the archer and stretched up to the chest.

As time progressed, medium and long bows were made, which could shoot harder and further.

But the length of an archer's arms puts a limit on the length of bows.

To increase shooting power beyond the maximum of a self bow, fletchers developed backed and fully composite bows,

of which the latter are actually shorter than longbows.

Here is a short overview:

- Self: Made of a single piece of a single material, traditionally wood or bamboo.

- Backed: Self bow reinforced with a backing of a different material. This slows down the straightening of the bow after a shot, increasing its effiency. A backing of sinew also increases the tension strength of the bow.

- Composite: A bow made of different materials, traditionally wood, horn and sinew, glued together. The composite construction packs more tension in the same bow length. Disadvantages are long and costly production, and detoriation when exposed to moisture.

- Recurve: Bow where the tips of the limbs bend forward, opposite to the general backward curve. This increases tension strength, energy efficiency and gives greater velocity to the arrow.

- Compound: Modern bow that uses pulleys to shift the main exertion from the end to the start of the draw, making the final aiming and release cost less effort and thus improving aim.

Some of the types can be combined.

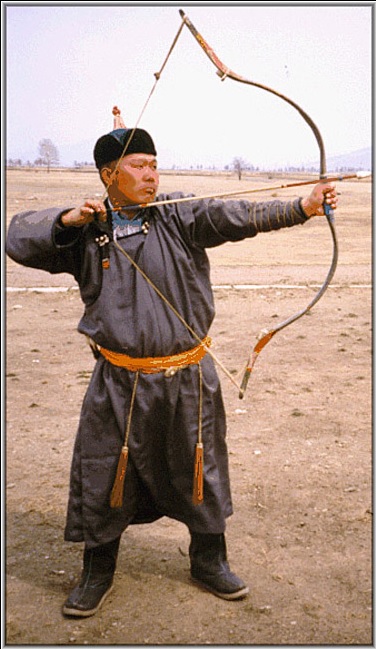

The recurved composite bow was and still is very popular in Asia.

In the hands of nomads, wielded from horseback, it was a formidable weapon.

In wetter climates, like in Western Europe, people stuck with self bows and backed bows.

The most famous one is the English longbow, which was very popular in England from 1275 to 1540 CE and phased out in the decades around 1600 CE.

It gained much status at the battles of Crécy and Agincourt.

Among handbows, there is great variation in bow length, draw length, tension strength, arrow length and weight, range and penetration power.

Ideally, the size and tension strength of the bow should match the stature and arm strength of the person that wields it,

but people can handle bows that do not match them with some loss of performance.

All these factors make it very hard to give accurate figures on the performance of these weapons.

In general, heavier bows require heavier arrows.

Arrows range in weight from about 10 grams to over a 100 grams.

Light flight arrows are fast and have great range.

Heavier war arrows have lower velocity, but take a larger percentage of the energy that the archer puts into a shot and also carry more momentum,

thus have a greater armor penetration capability.

Hunting arrows are fitted with broadhead points, designed to cut through flesh.

War arrows often need to penetrate armor and are fitted with shorter and stouter bodkin heads, or sometimes even blunted.

Crossbows

The Chinese and Greeks invented crossbows more or less simultaneously, around the 7th - 4th century BCE.

The Greeks developed them into field artillery weapons like the gastraphetes

and later siege catapults like oxybeles and lithobolos.

The Chinese also made hand-wieldable crossbows and even developed a repeating crossbow.

Crossbows were the most popular missile weapon in Europe from 1200 to 1460 CE and phased out in the decades around 1500 CE, when gunpowder firearms took over.

They remained popular as hunting weapons for centuries more, because they are silent.

Crossbows evolved from light to very powerful weapons.

During this evolution, ever more ingenious devices were developed to help the crossbowman pull the string up to full tension strength.

Several types can be discerned:

- The primitive crossbow. This weapon is tensed with both hands and arms. More advanced models have a stirrup at the fore-end of the stock, so the wielder can use the strength of one leg too.

-

The composite crossbow was introduced in Europe in the late 12th centrury CE.

This type is made of wood and horn, just like a composite handbow.

It has greater tensile strength and requires the help of a tension-tool to to tense fully:

- cord and pulley: increases stength by a factor of 2, in use until 1320 CE

- claw and belt: uses leg-power instead of arm-power, like with stirrup

- goat's foot lever: leverages arm strength by a factor of about 4 to 5, can be used by cavalry, in use 1350 - 1500 CE

-

The steel crossbow was introduced in the late 14th century CE.

This heavy crossbow requires heavy tools to bring it up to full tension strength:

- screw and handle: clumsy and tedious, but powerful

- cranequin: successor to screw and handle, can be used by cavalry, introduced 1480 CE

- windlass: powerful and faster than a cranequin, but heavier

Handbow versus crossbow

In military circles there is a long-lasting discussion about which weapon is better: the handbow or the crossbow. As can be expected, the answer to this question is that it depends, on several factors:

- Skill: A handbow requires skill to aim well and powerful bow requires great strength too. A crossbow can be used with little training or strength.

- Wielding: Cavalry cannot use longbows (too long) or heavy crossbows (too heavy) from horseback. Infantry does not suffer from these limitations.

- Rate of fire: Handbows can fire much more rapidly than even the lightest crossbow.

- Damage: A crossbow bolt has more kinetic energy and penetration power than an arrow from a handbow.

- Weather: Bowstrings tend to slacken when exposed to rain. Handbows, when wet, can still be used, though their firepower is lessened. Crossbows become useless, though if there is time, their strings can be restrung to bring them back to an operational state.

Weapon tables

The table below lists average effective combat statistics for a number of example bow types.

The list is by no means exclusive; it picks examples from a whole spectrum of bow types and sizes.

Units are taken from the International System of Units, so weights are in kilograms, lengths in meters, forces in Newtons and impacts in kilograms meters per second.

The only exception is the rate of fire, which is not listed in Hertz but 1/60 Hz alias shots / minute.

Sometimes a weapon is listed over multiple rows, each for a different arrow weight, as this can dramatically alter performance.

The weights given are typical examples; lighter or heavier arrows can often be used.

- Weapon: mass = mass and len = length of the bow itself (excluding tension-tools and ammunition). For handbows, length is measured when the weapon is strung.

- Ammunition: m = mass, len = length and diam = diameter of the arrows / bolts.

- Draw: forc = tension force, vel = initial arrow / bolt velocity

- Tension: tension strength.

- Range:

rng = range, vel = velocity, mom = momentum, erg = energy

- Point blank: Shooting straight at the mark. Estimated at a 2° shooting angle.

- Effective range: Maximum range where a skilled archer still has a decent chance of hitting a man-sized target. Estimated at a 5° shooting angle.

- Extreme range: Longest possible range without elevation or wind advantage. Shooting at a 45° angle.

- Fire rate: rate of fire: acc = accurate = well-aimed, inacc = inaccurate = shooting at random into a packed mass of targets.

- rem = remarks

| weapon | ammunition | draw | point blank | effective | extreme | fire rate | ||||||||||||||||||

| Handbows | mass | len | mass | len | diam | forc | vel | mom | erg | rng | vel | mom | erg | rng | vel | mom | erg | rng | vel | mom | erg | acc | inacc | rem |

| youth shortbow | 0.30 | 1.00 | 0.015 | 0.60 | 0.008 | 100 | 34 | 0.5 | 17 | 25 | 32 | 0.5 | 15 | 30 | 31 | 0.5 | 14 | 95 | 28 | 0.4 | 12 | 8 | 16 | (1) |

| hunting shortbow | 0.40 | 1.10 | 0.020 | 0.70 | 0.008 | 200 | 51 | 1.0 | 52 | 40 | 47 | 0.9 | 44 | 55 | 45 | 0.9 | 41 | 185 | 37 | 0.7 | 27 | 7 | 14 | (2) |

| hunting longbow | 0.60 | 1.65 | 0.030 | 0.70 | 0.009 | 300 | 56 | 1.7 | 94 | 45 | 52 | 1.6 | 81 | 65 | 50 | 1.5 | 75 | 220 | 41 | 1.2 | 50 | 6 | 12 | (3) |

| English war longbow | 0.80 | 1.80 | 0.050 | 0.75 | 0.011 | 500 | 62 | 3.1 | 192 | 50 | 57 | 2.9 | 162 | 80 | 54 | 2.7 | 146 | 265 | 44 | 2.2 | 97 | 6 | 12 | (4) |

| 0.090 | 0.80 | 0.013 | 50 | 4.5 | 225 | 40 | 48 | 4.3 | 207 | 55 | 47 | 4.2 | 198 | 205 | 41 | 3.7 | 151 | 6 | 12 | |||||

| Asian medium composite bow | 0.40 | 1.25 | 0.035 | 0.75 | 0.009 | 350 | 79 | 2.8 | 218 | 70 | 71 | 2.5 | 176 | 115 | 66 | 2.3 | 152 | 370 | 50 | 1.7 | 88 | 6 | 12 | (5) |

| 0.070 | 0.80 | 0.012 | 61 | 4.3 | 260 | 50 | 57 | 4.0 | 227 | 75 | 55 | 3.8 | 212 | 270 | 45 | 3.2 | 142 | 6 | 12 | |||||

| Asian heavy composite bow | 0.70 | 1.10 | 0.050 | 0.75 | 0.010 | 550 | 69 | 3.5 | 238 | 60 | 64 | 3.2 | 205 | 95 | 61 | 3.0 | 186 | 325 | 49 | 2.4 | 120 | 6 | 12 | (6) |

| 0.100 | 0.80 | 0.013 | 51 | 5.1 | 260 | 40 | 49 | 4.9 | 240 | 60 | 48 | 4.8 | 230 | 215 | 42 | 4.2 | 176 | 6 | 12 | |||||

| Japanese daikyu | 1.10 | 2.25 | 0.110 | 0.95 | 0.012 | 600 | 52 | 5.7 | 297 | 40 | 50 | 5.5 | 275 | 60 | 49 | 5.4 | 264 | 230 | 44 | 4.9 | 213 | 6 | 12 | (7) |

Notes:

- A light bow for women and youths, with less strength and length than adult men.

- Can be shot by adult men in good health and is suitable for killing small game and wounding unarmored enemies. The hunting bow is comparable with the 'sporting' longbow, which is longer but has similar tension, draw length and performance.

- Requires some strength and training and can be used to bring down large game or attack lightly armored enemies.

- Requires lots of strength and rigorous training and can penetrate medium thick armor. The draw 'weight' is average; heavier bows up to 65 kg are uncommon but used; extremes range up to 80 kg.

- This bow can be used efficiently with a wide range of arrow weights.

- 'Flight' bow. The draw 'weight' is above average but heavier bows up to 65 kg are used.

- The Japanese daikyu, which attained its final shape in the 16th century CE, has its grip at 1/3 of the length, rather than at 1/2 length as with most handbows. It is seconded by the shorter hankyu, "half-bow", and even smaller "kago hankyo", neither listed above. The Japanese bows are of composite build, using bamboo and wood.

| weapon | ammunition | draw | point blank | effective | extreme | fire rate | ||||||||||||||||||

| Crowssbows | mass | len | mass | len | diam | forc | vel | mom | erg | rng | vel | mom | erg | rng | vel | mom | erg | rng | vel | mom | erg | acc | inacc | rem |

| Chinese repeating crossbow | 1.3 | 0.60 | 0.015 | 0.20 | 0.008 | 225 | 39 | 0.6 | 23 | 30 | 37 | 0.6 | 21 | 40 | 36 | 0.5 | 19 | 120 | 32 | 0.5 | 15 | 24 | 40 | (1) |

| wooden crossbow | 2.8 | 0.85 | 0.0275 | 0.30 | 0.010 | 500 | 49 | 1.3 | 66 | 35 | 46 | 1.3 | 58 | 55 | 44 | 1.2 | 53 | 180 | 37 | 1.0 | 38 | 5 | 8 | (2) |

| eigth crossbow | 2.5 | 0.80 | 0.040 | 0.30 | 0.012 | 1000 | 53 | 2.1 | 112 | 40 | 49 | 2.0 | 96 | 60 | 47 | 1.9 | 88 | 200 | 39 | 1.6 | 61 | 3 | 4 | (3) |

| quarter crossbow | 3.0 | 0.85 | 0.0625 | 0.35 | 0.014 | 2000 | 60 | 3.8 | 225 | 50 | 55 | 3.5 | 189 | 75 | 53 | 3.3 | 176 | 250 | 43 | 2.7 | 116 | 2 | 3 | (4) |

| cavalry crossbow | 5.0 | 0.70 | 0.075 | 0.30 | 0.016 | 3350 | 72 | 5.4 | 389 | 60 | 64 | 4.8 | 307 | 95 | 60 | 4.5 | 270 | 310 | 46 | 3.4 | 159 | 2 | 2 | (5) |

| infantry crossbow | 7.0 | 0.75 | 0.085 | 0.30 | 0.017 | 4950 | 88 | 7.5 | 658 | 80 | 76 | 6.4 | 491 | 130 | 68 | 5.8 | 393 | 350 | 46 | 3.9 | 180 | 1 | 1 | (6) |

| siege crossbow | 8.0 | 0.95 | 0.090 | 0.35 | .0.018 | 5450 | 95 | 8.6 | 812 | 90 | 79 | 7.1 | 562 | 145 | 70 | 6.3 | 441 | 410 | 50 | 4.5 | 225 | 1 | 1 | (7) |

Notes:

- The rate of fire for the Chinese repeating crossbow excludes reloading. Its magazine houses 10 - 12 arrows, so at full speed is emptied in just 15 - 18 seconds.

- About the heaviest crossbow that can be strung comfortably without help. Suitable for hunting.

- Of composite construction. Needs a cord and pulley to be be strung.

- Of composite construction. Needs a goat's foot to be be strung.

- Made of steel. Needs a cranequin or windlass to be strung. A cranequin can be used from horseback, but is slower. Using a windlass, the crossbowman can achieve an inaccurate fire rate of 3 bolts per minute.

- Made of steel. Needs a windlass to be strung.

- Made of steel. Needs a windlass to be strung.

Accuracy

The chance of hitting a target with a bowshot depends on many factors, but the most measurable one is distance. At point blank, a novice archer has a good chance of hitting a man-sized target. More skilled archers are able to hit much smaller targets with a decent frequency. Beyond point blank, accuracy descreases rapidly for novice archers and slower for skilled ones. The "effective range" listed in the tables is about the maximum range where an average skilled archer still has a reasonable chance of hitting a man-sized target.

Damage

When calculating damage to an opponent, many factors come into play.

Broadhead arrows are good at piercing and cutting flesh, but perform poorly against armored opponents.

To punch through armor, an arrow with a narrow head like a bodkin is needed, but that causes less damage to the flesh behind it.

Broadhead arrows wreak damage by penetrating deep into flesh and causing bleeding.

They may also have the slower but equally deadly effect of infecting the wound with dirt or even poison.

Bodkin and blunt arrows do concussion damage even when they do not penetrate.

Bullets from a firearm mainly do concussion damage, both on impact and when penetrating flesh.

Against opponents with little or no armor some of them are actually overpowered,

entering at the front and exiting at the back without transferring all their kinetic energy to the wound.

With arrows and bolts, this is seldom the case.

A good measure for damage seems to be either arrow/bolt energy or momentum minus armor protection,

which means that low energy/momentum shots have zero effect against heavy armor.

A bolt from a heavy crossbow at close range will punch straight through about any armor except strong plate,

while a shot from a shortbow has difficulty penetrating even sturdy clothing.

Common misconceptions

Compared to modern archery, there is little factual data available on the performance of historical bows. This text is a mix of hard experimental data, descriptions from the past, applied simple physics and estimated guesses. I think that the numbers are quite accurate, though they may surprise some readers, as a lot of misconceptions circulate over the internet. Here are a few:

- Misconception: Every bow has a point blank range. Arrows / bolts fly level up to that range and afterwards start to fall. Truth: Gravity kicks in at the moment that the arrow / bolts leaves the bow, thus it starts falling immediately. You always have to aim at least slightly upward to hit a target at the same height that you are shooting from. Point blank is the range where the target lines up with mark, nothing more.

- Misconception: Shots from crossbows are much more powerful than handbows. Truth: It depends on the 'heaviness' of the bows. On average a crossbow bolt carries more energy, but handbows with a lot of draw weight clearly outclass lighter crossbows.

- Misconception: Crossbow bolts are much heavier than handbow arrows. Truth: Bolts are about half as long as arrows, but thicker, ending up with about the same weight.

Arrow Flight Simulator

Much of the data in the weapon tables has been calculated by an Arrow Flight Simulator. This utility calculates the flight path of an arrow, depending on several configurable parameters, including air resistance.

References

- https://www.archerylibrary.com/books/ has texts old texts on archery, written by people who actually made and used bows.

- An good starting source on information on crossbows is Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey's "The Crossbow", ISBN-10: 1-60239-010-X / ISBN-13: 978-60239-010-2.

- A wealth of short articles on both the history and mechanics of archery, can be found at the website of the Sagittarius Archery Club: http://margo.student.utwente.nl/sagi/artikel/.

- Adam Karpowicz has made replicas of and done tests with Asian composite bows. See http://www.ottoman-turkish-bows.com/.

- A collection of articles on arrow flight ballistics: https://sites.google.com/site/archerybibliography/arrows-1

- Whitney King has done measurement of a real arrow flight trajectory, including air drag: https://sites.google.com/site/technicalarchery/technical-discussions-1/full-trajectory-calculator-for-riffles-muzzle-loaders-and-bows