In modern times, with engine-powered trains, ships, cars and even airplanes, travel is seldom difficult, often relaxing. In the old days, when people walked on foot, rode animals or traveled in sailing ships, things were quite different. On the basis of several cases, this article describes how such travel was like and what the influence of weather, terrain and even geography was.

The wheel

History books often mention the 'invention of the wheel' as if it were a major technological revolution.

In reality it was probably invented in the ice age, tens of thousands of years before urban civilization took off.

For millennia, it remained a toy, because our ancestors had no real use for it.

In the 5th millennium BCE carts and wagons appeared because long distance trade grew and with it the desire to transport large loads efficiently.

This technology did not only involve the wheel but also the axle.

The latter is the more difficult and more important invention of the two.

Wheeled vehicles can transport loads 10 to 20 times heavier than those carried on a back.

Humans can pull them, but draft animals are stronger.

A sturdy horse can pull a cart or wagon with a load of about 1 ton.

However wheeled transports have their drawbacks.

First of all they need relatively smooth, hard and level surfaces, like proper roads.

Going uphill requires extra effort and downhill too, as many pre-industrial vehicles had only primitive brakes, or none at all.

Ancient and medieval roads, and bridges too, where scarce.

The vast majority were just tracks that were mostly clear of obstacles.

These did not present a smooth surface, hindering the wheels.

Yet they were better than nothing.

On frozen ground wheel efficiency is about 50%; through dry pasture 35% - 40%; wet pasture 25% - 30%; loose soil 20%; mud even less.

Extensive use of tracks caused erosion, making them adopt a convex shape that sucked in water.

Many such 'holloways' were so narrow that traffic had to be limited to one way at the time.

This drastically reduced the efficiency of wheels, forcing wagoners to do with lighter loads.

Though rough by modern standards, paved roads held their own far better bad weather.

Only powerful states could afford to build them, and then only a few along major routes.

The prime example is the transport network of the Roman empire, the roads of which were made up of several layers.

These were not convex but concave, to drain water sideways, and had hard surfaces with cobblestones on top.

Draft animals which have to work hard cannot walk fast for long periods.

The average speed of a horse-drawn cart is some 30 kilometers per day; wagons with heavy loads only 20.

Donkeys, oxen and such go even slower.

The animals must be able to graze during rests and also be fed extra grain.

If fodder is not available, because the travel is done in winter or in barren regions,

it must be loaded in advance and carried on the vehicle, subtracting from the effective load.

For all the reasons listed above, plus the discomfort of the wagoners themselves,

our ancestors mostly avoided travel in deserts, mountains or winter unless they had to.

Qhapaq Ñan

Neither South-American Inca nor their predecessors made use of the wheel for transport.

The terrain in and around the Andes is for most part unsuitable for carts and wagons: rugged, many steep slopes, thick jungle.

Also, pre-Columbian America lacked strong draft animals like horses, oxen and water buffaloes; they had only lighter and weaker llamas and alpacas.

The roads were reserved for royalty, armies, diplomatic messengers and designated caravans.

Urgent messengers were relayed by runners, each of whom ran a stretch of 1.4 kilometers from one waystation to the next.

Using this system messages and small goods could travel 240 kilometers per day.

Despite the strict rules, commoners used the roads also, as policing their long lengths all the time was impossible.

Next to the many runner waystations there were also inns, located a day's walking (not running) apart.

Unlike Roman roads, which were often straight, the Inca roads were more often forced to adapt to the terrain.

Rivers were crossed with ferries or bridges, chasms with suspension bridges made of rope; marshes paved with causeways.

On flat terrain the roads were about 4 meters wide, though major roads near cities could be as wide as 35 meters.

Along steep slopes the width was as little as 1 meter.

However where possible rough terrain like deserts, marshes and high mountains was avoided.

Some roads were paved, others were simply tracks of packed earth.

To keep them in good repair, the Inca installed gutters or low protective walls.

In mountains they created shallow stairs with steps or cut short tunnels through rock.

The roads required intensive maintenance.

Wooden bridges had to be renewed every 8 years; rope bridges every 2 years.

The Taklamakan case

A famous travel route was the Silk Road, where silk and other goods from China were transported overland through Asia to the west and other trade goods went in the opposite direction.

Of course there was not a single road, but a network of them, which changed over time too.

A serious obstacle for travelers was the Taklamakan desert in Central Asia.

Very few people took the shortest route straight through the desert.

After all, it is a desert, barren, hostile and dangerous.

You can get lost there and die of thirst or hunger.

The two main routes through the desert skirt its southern and northern edge respectively.

There one can navigate by keeping the mountains in sight and more importantly, there are oases with fresh water.

There is a third route though.

Not through the desert, not even along its edge but around it, through Dzungaria and the Alataw Pass a.k.a. Dzungarian Gate and Zhetsyu.

It is a steppe route, and a detour too.

The desert routes were favored by traders, the steppe route by migrants.

There were several reasons for that.

Traders did not like the steppe, which is a vast plain where bandits coukd pop up from anywhere and rob you of your precious goods.

The desert may be tough terrain, but there you could travel from one oasis to another, or maybe stop at a caravansary in between.

At these stops there was water and food and there were walls and soldiers to keep you safe at night.

As other traders stopped there too, all kinds of goods and services were available and you could pay with money or part of your load.

Migrants had different needs and possibilities.

They traveled in large bands with plenty of warriors to frighten off bandits.

They did not have much to trade but many mouths to feed, which would quickly exhaust the supplies of a caravan stop.

In the steppe, which is much greener, hunters could hunt game and more importantly, horses and livestock could graze, grow fat and provide enough food.

The Second Horseman of the Apocalypse

Making day marches through fields is awkward, through rugged wilderness even more restrictive.

Therefore large groups of people, most commonly armies, stuck to the roads.

This forced them to march in narrow, long columns.

Often they split up in several columns, each taking a different though parallel route.

Only when battle was imminent did these columns coalesce and form a wide front.

The need to keep soldiers marching in step so as not to obstruct each other,

the necessity to make camps because wayside inns and taverns could not house such large numbers

and even the length of the columns all made armies march slower than small parties or individuals.

On good roads and with good weather a Roman army on foot marched 3.75 kilometers per hour (including rests),

for 6 Roman 'summer' hours, equivalent to about 8 standard hours.

This way they could cover 20 Roman miles, which is 30 kilometers, per day.

The length of the columns could be a limiting factor.

On a good road soldiers marched 6 men abreast, on lesser roads 4, on smaller tracks even less, down to just 1.

With each row at least 1.5 meters meters apart and some distance between units too,

this means that for example a large army of 30,000 men would create a column at least 8 kilometers long.

At standard Roman marching speed this meant that the soldiers at the rear started marching more than 1.5 hours after those at the front.

As marching at night without street lights is certain to get soldiers stumble themselves into injuries and units getting lost, pre-industrial armies marched only in daylight.

In winter time, at high latitudes, the days are too short to have the entire army make a full day march and have everybody arrive in the next camp before dark.

There were several other reasons to avoid the winter when marching.

Winter weather is colder and/or wetter, turning dirt roads bad, reducing speed.

Also, soldiers on the march very often do not have the luxury of sturdy houses to spend the night; instead they have to do with tents or not even that.

Thus poorly protected from the weather they are prone to diseases, which throughout history killed more soldiers than fighting has.

Finally, especially in late winter, food was scarce, giving rise to the danger of starvation.

For all these reasons high 'campaign season' was summer, extending into spring and autumn.

Armies are composed of strong men in the prime of their lives.

Yet there are limits to what a man can carry.

Throughout history, the maximum load for soldiers for anything but short stretches has been 30 - 35 kilograms.

About half of that is weapons, armor and other gear; the rest can be used for supplies.

Heavy soldier labor requires about 1½ kilograms of food per day, so a soldier can carry about 10 - 11 days of food supplies.

This means that the range of unsupported armies on foot is limited to 300 - 330 kilometers.

Pre-industrial armies often used baggage trains to carry food and other supplies, but as a draft animals require food themselves too,

their effectiveness regarding operational range was limited, though they lessened the burdens on the soldier's shoulders.

Most such armies depended on water transport and/or supply dumps along the way, severely limiting the number of possible routes to the battlefields.

An exception to the sluggish infantry armies were raiders.

Often mounted on horses, they were faster in the first place.

Nomad armies drove herds of cattle with them as a kind of mobile larder.

True raiders went a step further and lived off the land, by plundering the countryside around them.

This way, for example Mongol armies could cover 65 kilometers per day without wearing themselves out.

The Himalayas

A good defense against invading armies is hostile terrain.

The large subcontinent of India is an example, shielded by mountains in the north and sea in the south.

This did not deter all raiders and conquerors, several of whom invaded, all from the northwest.

Higher mountains to the east and especially north, and the rugged terrain behind those,

limited mountain travel to a few traders, pilgrims and adventurers.

Mountains present formidable barriers, even to modern cars.

Mountain travel routes have to zigzag around peaks and glaciers, often but not always following river valleys.

In the truly high mountains altitude comes with several problems.

Every 1 kilometer higher up the air pressure drops by 10% and the temperature by 6.5° Celcius,

making breathing and keeping warm hard.

Yet travelers cannot always choose to stay as low as possible, in the valleys.

The gradient of the slopes is an important factor.

Wheeled vehicles pulled by draft animals are usually limited to a gradient of 5%,

though with good harnesses and brakes can occasionally handle slopes up to 10%.

Beyond that, which is common in the high mountains, travelers on foot and especially pack animals must take over.

A sturdy pack animal can carry around 90 kilograms of load, though that was often lightened to 70 to allow the animals to cope with the gradient.

Also, several lower areas are not gentle valleys but steep gorges where rivers trickle through in the dry season but torrent in the wet season.

Therefore routes through the Himalayas often cross a few mountain passes that lie at altitudes of more than 5 kilometers.

Though they are often the sole means of crossing difficult mountains,

bad winter weather with even lower temperatures and lots of snowfall renders them inaccessible for part of the year.

Some passes could not be crossed for 3 months, others for up to half a year.

Egypt

Roads are famous landmarks, but waterways were much more important than roads.

Ships can carry much larger loads than humans, animals or even wagons can, at low yet acceptable (pre-industrial) speeds.

Unlike pack animals, they do not require food to keep going.

As a result, river transport was often 10 - 20 times cheaper than land transport.

In Egypt the choice between the two was a no-brainer.

Most of the country is desert; almost all people, agriculture, economic activity and transport was and still is concentrated in a narrow strip that surrounds the river Nile.

The ancient Egyptians called the land around the Nile the 'Black Land', fertile and seat of life; the surrounding desert the 'Red Land', barren and hostile.

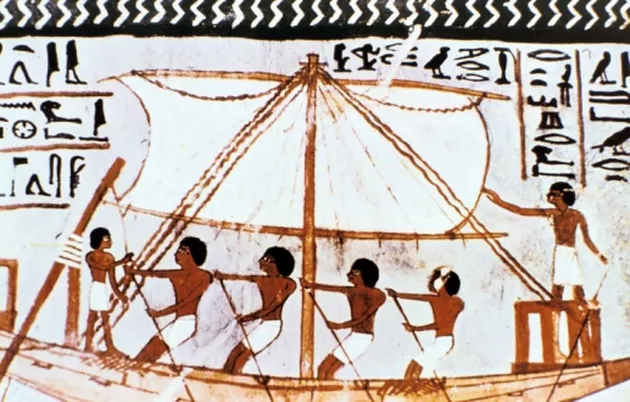

Sailing may have been invented in Egypt.

The first ships of were made of tightly packed bundles of reeds, available at the river itself.

Later wooden hulls took over, at least for larger ships.

They used the current to float downstream.

Upstream, the ships could be sailed, rowed, punted or pulled by land-based draft animals.

Even the latter was more efficient than using the animals as pack carriers, as pulling is easier than their carrying.

Average speeds varied with the currents and winds, between 35 and 100 kilometers per day downstream and between 30 and 90 upstream on multi-day journeys.

The largest of even the ancient ships could carry very large loads, for example stones for the construction of the famous pyramids, up to several hundred tons.

The disadvantage of river transport it that it is limited to the navigable parts of the waterways, and to the waterways themselves.

Sandbanks, rapids and waterfalls, even bridges, watermills and fishing weirs can block ships hard,

though small boats can portaged past these obstacles.

For larger ships only the lower parts of a river can be used, not the small, rapid streams up in the mountains,

and for crossing the mountains themselves land transport is a must.

In Egypt, Nile river transport became difficult at the first cataract, near the modern town of Aswan, the natural border between Egypt and Kush.

Further south there are five more cataracts.

Viking ships

The ships that were built by the vikings in the Middle Ages are almost as famous as the vikings themselves.

They were clinker-built galleys with low freeboard and shallow draft.

The basic design could be varied, giving rise to sleek warships, broad traders, coastal cruisers and others.

They were good for raiding, trading and of course sea travel in general.

However a voyage in a viking ship was no pleasure cruise.

The ships had a single deck, so the crew was exposed to the elements all the time,

suffering heat, cold or wetness whenever the weather felt like it.

People could vacate their bowels only by dropping their pants and hanging their bottom overboard.

There were no refrigerators or cans to preserve food or even fresh water, which gradually spoiled.

Navigation was difficult without GPS or even compasses and chronometers.

Sailors observed coastlines, currents, water color, drift ice and seaweed, winds, birds, sun and stars instead.

Yet ships could and sometimes did get lost in the wide blue.

Storms could very well sink ships, especially in the open sea or ocean.

And all through the voyage the crew was confined to the small space of the ship,

with nowhere else to go if circumstances became unpleasant or dangerous.

Therefore most shipping routes where not straight lines from one harbor to another.

Medieval captains preferred to sail close to land, so they could seek shelter, re-orientate, resupply and/or repair when the need arose.

Medieval travelers in general took more extreme measures: they avoided sea travel when possible.

Despite all the hardships and dangers ships were very useful.

Viking warships carried about 30 - 40 warriors, traveled 100 miles per day in good wind and could be rowed upriver (at much slower speed).

Traders were slower but could carry cargo of several tens of tons, far more than land transport.