Before the advent of firearms, body armor was an essential part of the defense of a warrior. All armor is a compromise between protection on side and factors like weight, flexibility on the other side. It may have been heavy, hot and expensive, but those are small nuisances in a fight for life or death. This text gives a short overview of armor types. Only general properties are outlined, but these can be used as a basis for a RPG armor system, ranging from simple to elaborate.

Body parts

Armor can cover the entire body, or just part of it.

Below is a list of body parts and armor parts that cover them.

As you can see, English armor vocabulary is heavily influenced by French.

Not every body part is considered equally important, so each has been given a rating.

The importance rating concerns how important the body part is relative to the whole.

The total for all body parts combined is 100%.

This is not equal to the surface area or weight; head and torso are more important than limbs.

The weight rating gives the weight relative to a set of armor that covers the entire body.

The values include importance; torso armor is about twice as thick as limb armor, head armor three times as much.

This assumes that the armor covers body parts completely, which was not always the case.

For example ancient shin guards covered only the front of the lower legs, not the rear.

| Name | Protects | Importance | Weight |

| coif, helmet | head | 20% | 12% |

| aventail, bevor, gorget | neck | 4% | 2% |

| aventail, pauldrons, spaulders | shoulders | 3% | 4% |

| cuirass | torso | 50% | 39% |

| faulds | groin | 3% | 4% |

| brassarts, rerebraces, vambraces | upper arms | 4% | 7% |

| bracers, gauntlets, vambraces | lower arms | 3% | 6% |

| gauntlets, gloves | hands | 2% | 4% |

| tassets, chausses, cuisses | thighs, upper legs | 5% | 9% |

| greaves | lower legs | 4% | 8% |

| boots, sabatons | feet | 2% | 5% |

Materials

Fibers

All cloth armor consists of several layers of cloth made of linen, wool or cotton, which are quilted or maybe twined together.

Linen is the toughest and best water-handling of the three.

It can be worn as an undercoat for heavier armor or as an independent armor itself.

The former is called aketon, arming doublet or several other names; the latter is named gambeson,

though the names are often mixed up.

The standalone variant is specialized, much thicker, especially in places where protection matters the most.

Cloth is always composed of several layers, from just a few up to 20 - 30.

Some have some layers of cloth with stuffing, preferably wool, in between; others consist of quilted layers only.

As armor, it has limitations, but is cheap and quite effective in some aspects.

All cloth armor consists of several layers of cloth made of linen, wool or cotton, which are quilted or maybe twined together.

Linen is the toughest and best water-handling of the three.

It can be worn as an undercoat for heavier armor or as an independent armor itself.

The former is called aketon, arming doublet or several other names; the latter is named gambeson,

though the names are often mixed up.

The standalone variant is specialized, much thicker, especially in places where protection matters the most.

Cloth is always composed of several layers, from just a few up to 20 - 30.

Some have some layers of cloth with stuffing, preferably wool, in between; others consist of quilted layers only.

As armor, it has limitations, but is cheap and quite effective in some aspects.

Leather is sometimes used as undercoat for other types of armor, but also standalone. The leather used in clothing is too soft for armor. More common are tanned and waxed leather which are much more water-resistant than untreated leather, yet still not very tough. To make leather resilient enough it must be heated also, preferably together with wax, certain acids or oil. The latter variant is called "cuir bouilli". Heat-treated leather is harder but also more brittle than normal tanned leather. Similar to heat-treated armor is leather that is lacquered, a technique that was mainly used in Asia. Like cloth, leather armor usually is a padding of several layers.

Metals

When metalworking was invented, metals quickly surpassed fibers. But soft armor remained in use as material for undercoats, to protect less vital areas like limbs, or the whole body if money was short supply.

Early metal armor was made of copper, a relatively soft metal that was easy to work. Copper was quickly supplanted by the tougher bronze, usually in a mix of up to 88% - 90% copper and 10% - 12% tin, called 'classic' bronze. The next revolution was iron working, which required an entirely different smithing process at much higher temperatures. Early iron was of low quality, but less scarce than the copper and tin needed to produce bronze.

The final step was to transform iron into steel, making it much harder. Smiths gradually improved their methods of making wrought iron (too little carbon content, soft) and cast iron (too much carbon, brittle) into steel (just enough carbon). Ancient and medieval steel was better than bronze, but still less than the best factory-produced modern steel, which unlike the pre-industrial steel is almost free of slag. In the table below, mild steel has about 0.2% carbon, mild steel 0.5% and finally wootz steel 1.2% carbon plus some other important hardening elements.

Other materials

Though most armor was made of fibers and metals, other materials were used too. Examples are animal horn or shells, expensive but hard, and wood, inferior but widely available. The Chinese even invented paper armor, which is surprisingly effective and lightweight, but not durable. These materials are not detailed here because there is too little data available for them.

Properties

The table below lists effective properties for common armor crafting materials. It assumes late medieval smithing technology, so large bloomery furnaces but no blast furnaces yet.

- The data given for cloth and leather is not for a single layer, but a padding of several layers. The number listed is an average.

- The thickness listed is the average thickness, in millimeters; again real thickness may vary.

- Weights are only relative, with iron/steel normative at 100. They take the number of layers into account, so for example the weight of 20 for padded cloth is for 20 layers.

- Protection is estimated Vickers hardness. Most metals have three protection scores: one for the pure metal, the second after the metal has been worked, the third after it has been worked to its maximum. Improving copper, bronze and iron was cold working, through hammering and cold hardening, which is relatively straightforward for a skilled smith. Hardening steel was done through quenching, tempering and/or case hardening, which may improve but can also ruin the armor. Most steels were not worked to their maximum hardness, as this made them brittle too. All this made worked steel much more expensive than pure steel. Wootz steel, because of its natural qualities, was seldom quenched, simply air cooled.

| Material | Bulk | Protection | Cost | Durability | |||||

| Layers | Thickness | Weight | Pure | Worked | Master | Materials | Labor | ||

| padded cloth | 20 | 12.0 | 20 | n.a. | 100 | n.a. | very cheap | cheap | very low |

| quilted cloth | 20 | 12.0 | 40 | n.a. | 160 | n.a. | cheap | cheap | low |

| leather | 2 | 6.0 | 25 | n.a. | 100 | n.a. | cheap | modest | low |

| copper | 1 | 1.5 | 113 | 35 | 105 | n.a. | very expensive | modest | high |

| classic bronze | 1 | 1.5 | 108 | 90 | 250 | n.a. | very expensive | modest | very high |

| wrought iron | 1 | 1.5 | 100 | 70 | 150 | n.a. | cheap | modest | medium |

| mild steel | 1 | 1.5 | 100 | 110 | 180 | 220 | modest | (very) expensive | high |

| medium steel | 1 | 1.5 | 100 | 165 | 250 | 350 | expensive | (very) expensive | high |

| wootz steel | 1 | 1.5 | 100 | 300 | 350 | n.a. | very expensive | expensive | high |

Construction types

Descriptions

Most fiber armor are simply a stack of layers, but metal armors have a wider variety of construction types. All metal armors require some kind of undercoat, like a light gambeson or arming doublet, to protect the skin from chafing and provide attachments for the outer armor. This is considered to be part of the armor. An undercoat for the torso, groin, shoulders and arms weighs some 2 kilograms on average, as it is not so thick as a standalone gambeson. Below is a list of different construction types, more or less in chronological order of development.

| Scale | Scale armor is made from studs (called scales) that are attached to both each other and the undercoat. The scales are often triangular or U-shaped, and overlap each other from top to bottom. The result looks like the skin of a fish, hence the name 'scale' armor. It is also called 'leaf' armor. An example is the Roman lorica squamata. Scale armor is known since ancient times but was largely supplanted by lamellar and mail, which offer better protection for the same weight. Yet scale armor was not totally obsoleted, as it breathes well and is almost as flexible as mail. |

|

| Lamellar | Like scale armor, lamellar armor is made of studs (called lamellae). The difference is that they are only connected to each other, not to the undercoat. Also, their shape is often simply rectangular. They can partially overlap like scales, usually upward instead of downward, or be aligned next to each other. Lamellar armor takes more effort to construct than scale, but is generally easy to maintain. In most lamellar armors, the lamellae are laced together with strings. These are somewhat vulnerable to damage, but easy to repair, even in the field by a common soldier. Another method is riveting them together, creating a tighter and sturdier whole. The more the studs overlap, the better the protection, but worse the airflow, flexibility and maintenance. The origin of lamellar armor is ancient and it has remained popular in Asia for millennia. |

|

| Splint | Splint armor resembles brigandine, but here the studs are expanded into strips. The most common method of assembly is riveting them into the undercoat, without any outer layer, like brigandine armor. It is most commonly used to protect the lower arms and legs, where strips are aligned with the limbs. Splints can be positioned close together for good protection, or with some space in between for more flexibility. |

|

| Laminar | This type of armor consists of (usually horizontal) bands that overlap each other. They are connected by a combination of straps and riveting. Other names are 'banded' and 'segmented' armor. The Roman lorica segmentata is an example with relatively loose fitted bands. Laminar armor was largely superseded by plated mail when that type of armor was introduced. |

|

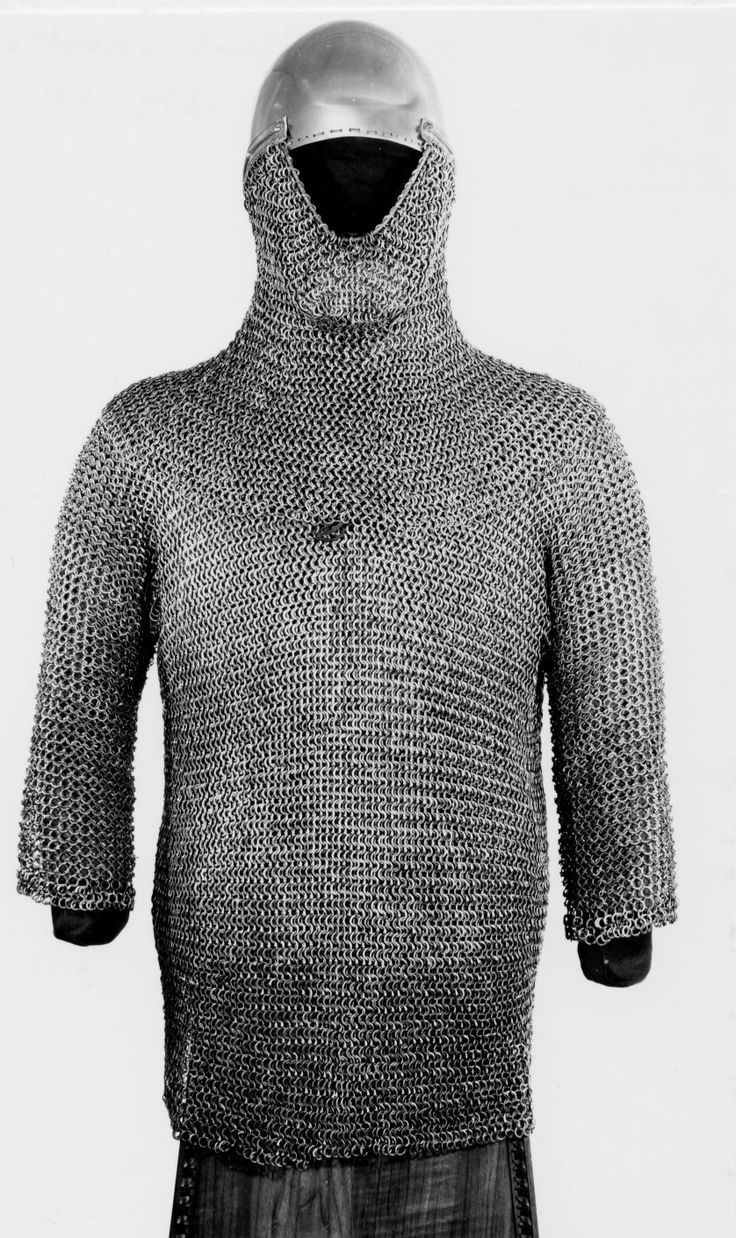

| Mail is often named 'chain mail', though that name is a Victorian invention. 'Mail' is the official term. It consists of interlocking metal rings. Mail protects well against cuts, but is weak in protecting the head and joints. However combined with padding underneath it protects the wearer quite well. Also it is very flexible to wear and move in, and can be cleaned easily by rolling it around in a bag filled with sand. These qualities have made it the most popular type of armor in history. The protection offered by mail depends very much on the material, the weave density and ring thickness and also upon the type of construction: riveted is better than welded is better than butted. Almost all historical mail is riveted. Nearly all mail has a 4-in-1 pattern, though denser, sturdier and more rigid 6-in-1 was occasionally used. A "byrnie" is a waist-length mail shirt, a "haubergeon" reaches down to mid-thigh and a "hauberk" down to the knees. Mail may also be extended upwards with the addition of a "coif" to protect the head, though usually a proper helm is worn over that. |

|

|

| Coat of plates | This type consists of medium sized metal plates that are sewn onto an undercoat. It is an intermediate type of construction from the small scales, lamellae and rings of earlier armor types to full plate armor. Coat of plates is often confused with brigandine, but its plates are larger and the method of attaching them to the undercoat differs. It is the somewhat more primitive forerunner of brigandine. |

|

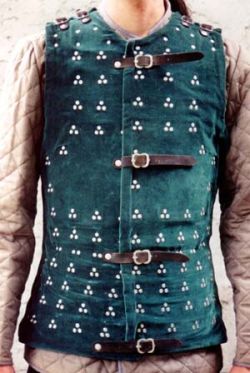

| Brigandine | Brigandine armor consists of small to medium metal plates riveted into a coat, with a lighter undercoat on the other (inner) side. The studs can be adjacent or overlapping. It is often labeled as the poor man's plate armor, though more flexible and quite effective overall. The name brigandine derives from brigand and is often confused with its modern equivalent of bandit, but brigand originally meant foot soldier, which is where the association comes from. |

|

| Plated mail | As the name denotes, this type is a mix between plate and mail. It is not a suit of armor where some parts are plate and others mail, but rather medium sized plates joined together by mail all over. The plates can be adjacent like in lamellar armor, or overlap like in laminar. This type is popular in Eastern Europe and the Middle East. |

|

| Plate | Plate armor is made up from large plates, "lames", all custom made to fit specific parts of the body. The plates are linked together by rivets and straps. If well-crafted it is superior to all other types. Average thickness of plate varies from 1 mm (limbs) through 2 mm (cuirass) and 3 mm (helmet). A Renaissance bullet-proof cuirass could be even thicker, in places some 4 mm or even more. Plate uses less material and can be made in less time than mail, however it requires relative advanced steel late medieval smithing technology to be able to craft large lames. A full suit must be made to fit the wearer snugly and this requires a very skilled smith. Thus it is more expensive than other armor types. Simpler plate armor variants like 'munitions' armor exist too, not covering the entire body and using inferior steel. These are less effective but cheaper, suitable for mass production. |

|

Properties

The table below gives a rough categorization of the pros and cons of different types of armor.

Note that it is a mix of materials (for fibers) and construction types (for metal armor).

Most 'burden' properties are self-explanatory.

Comfort is a mix of breathing, water resistance and weight distribution.

Mail and plate can be applied to all parts of the body, including head, hands and feet, but most are suitable for the large parts only.

Legend for appliance: ⬛ = suitable, ⬕ = somewhat suitable, ⬚ = unsuitable.

| Type | Protection | Appliances | Burden | Cost | |||||||

| General | Torso | Arms | Legs | Flexibility | Comfort | Cleaning | Loudness | Purchase | Durability | Maintenance | |

| Cloth | poor | ⬛ | ⬛ | ⬛ | medium | awkward | difficult | quiet | cheap | low | fair |

| Leather | poor | ⬛ | ⬚ | ⬚ | stiff | awkward | difficult | moderate | cheap | medium | laborious |

| Scale | moderate | ⬛ | ⬚ | ⬚ | flexible | awkward | difficult | very loud | modest | medium | fair |

| Lamellar | good | ⬛ | ⬕ | ⬕ | stiff | awkward | average | loud | modest | medium | fair |

| Splint | moderate | ⬚ | ⬛ | ⬛ | flexible | awkward | average | quiet | cheap | medium | fair |

| Laminar | good | ⬛ | ⬚ | ⬚ | stiff | awkward | difficult | very loud | modest | medium | fair |

| moderate | ⬛ | ⬛ | ⬛ | flexible | snug | easy | loud | expensive | medium | fair | |

| Coat of plates | good | ⬛ | ⬚ | ⬚ | stiff | awkward | average | loud | modest | high | laborious |

| Brigandine | good | ⬛ | ⬚ | ⬚ | medium | awkward | average | loud | modest | high | fair |

| Plated mail | good | ⬛ | ⬛ | ⬛ | medium | moderate | difficult | loud | expensive | high | laborious |

| Plate | very good | ⬛ | ⬛ | ⬛ | stiff | awkward | difficult | very loud | very expensive | very high | very laborious |

Weight

A heavy full body set of metal armor, regardless of construction type, weighs about 20 kilograms. This excludes the helmet (see below) but includes neck, limbs, hands and feet. Such full suits were rare. Simple cuirasses, protecting just the torso, groin and possibly arms and upper legs were more common. They are lighter, cheaper and allowed greater freedom of movement, while still protecting the most important parts. For example an average heavy mail byrnie, protecting neck, shoulders, torso, groin weighs about 9 kilograms; a haubergeon, extending to upper arms and thighs, 11 kilograms; a hauberk, further extending to lower arms and upper legs, 14 kilograms. A mail coif for just the head weighs just 1 kilogram; a large integrated coif and aventail that provides cover from the head to the shoulders and upper torso 3 kilograms.

Helmets

| Name | Description | Protection | Weight | Vision | Hearing | Purchase |

| Skullcap |

Covers only the upper part of the skull.

Examples: skull cap. |

5 | 1 | clear | clear | cheap |

| Open helmet |

Skull cap with additional protections like nose guard, face mask, and/or cheek guards, neck protection.

Examples: (classical) Illyrian helm, Chaldician helm, Attican helm, Roman helmets; (medieval) spangenhelm, nasal helm, burgonet, Japanese kabuto. |

10 | 2 | clear | clear | modest |

| Half-open helmet |

Covers the entire head but leaves a T- or Y-shaped area in the face open for seeing and breathing.

Examples: (classical) Korinthian helm; (medieval) barbute. |

15 | 2.5 | clear | muffled | modest |

| Closed helmet |

Covers the entire head.

Usually equipped with a movable visor.

Examples: close helm, bascinet / hounskull, armet. |

20 | 3 | limited | muffled | expensive |

Variations

Bulk

Armor that is considered to be too weak can be made tougher by simply making it thicker, which of course increases the weight. Likewise too heavy armor can be made lighter by making it thinner. Most professional armor is already tuned this way with for example a thickness of 1 mm on the limbs and back of the torso, 2 mm on the front of the torso and 2 - 3 mm on the head. Construction types that are made from small pieces can also be made denser or sparser instead. Mail can use smaller/larger links for a denser/sparser weave; scale and lamellar can have their scales/lamellae overlap more or less; splints can be set closer together or further apart. An acceptable range for thickness/density and weight is ⅔ - 1½ times the average. Lighter than ⅔ or more than 1½ is impractical. Greater sturdiness affects protection positively and weight, flexibility, breathing and cost negatively; lesser the reverse. Those relations are more or less proportional to the sturdiness. Vision, hearing, cleaning, loudness, durability and maintenance are but little affected.

Double armor

It is possible and often even desirable to wear multiple pieces of armor over each other. The aketon that prevents chafing is a prime example, but a third layer over the outer metal is also possible. Mail is the prime candidate for such combinations because of its flexibility. Gambeson with mail over it was common; mail under scale or lamellar, or mail over lamellar less so. Mail combined with plate was a common sight in the 14th century when plate was not fully developed; afterwards plate could stand on its own and extra mail was just a hindrance. More than three layers (aketon + mail + other) was impractical. Double armor was used only for the torso and groin, never for the limbs, which need substantial freedom of movement. Like increased bulk, double armor affects protection, weight, flexibility, breathing and cost.

Mixed armor

Armor can be mixed.

For example in ancient Greece the linothorax, a kind of quilted cloth armor, was sometimes studded with bronze plates.

Combining splint armor on the limbs with another construction type on the torso was also common.

Many sturdy constructions that protected the torso and the shoulders used mail to cover the armpits.

Calculation of the properties of these variations is beyond this document.

Not all armor pieces can be combined freely.

For example pieces of full plate armor are designed to be used together, not separately.

They can be combined with other types of armor, but don't fit well, so in that case are less effective than they can and should be.

Use in role playing games

In combat without firearms or magic, just plain old melee and missile weapons, armor is a vital part of defense.

It does not make you less likely to be hit, like Dungeons & Dragons states, but instead absorbs impact energy, decreasing wounds.

The price that the armored warrior pays is encumbrance and hampered senses.

But how much?

Using the data listed above, you can build many different armor 'systems'.

Players who want detail should go for 'piecemeal armor', where different parts of the body are protected by different pieces of armor.

Attacks should be directed at those specific parts of the body and even the type of attack (thrust / slash / crush) should be specified too.

You can calculate the protection value of the armor by multiplying: construction type x material x thickness x quality.

Similar formulas can be set up for other attributes like weight, freedom of movement, loudness, hampering of the senses and cost.

If you do not want so much detail, you can calculate an overall armor score by rating the whole as the weighted average of the parts.

For instance: This value 8 helmet combined with this value 6 cuirass, which also covers the shoulders, without any other protection,

has a total value of ((8 x 20%) + (6 x (50% + 3%)) / 100% = 4.78, rounded to 5.

If even that is too much work, you can use predefined sets of armor and have each rated at a fixed value.

For instance: This humble scale cuirass has an armor rating of 2, while this splendid royal suit of plate armor rates at 9.

References

- Good introduction: http://www.medievalwarfare.info/armour.htm

- The museum of the Salish has a nice introduction on armor: http://www.temixwten.net/biblio/IQP-EvolutionOfMaterials-MedievalEra.pdf.

- Replicas, reviews, articles and discussions on medieval armor and weapons can be found at https://www.myarmoury.com/.

- Matthew Amt has a nice collection of information and hyperlinks about ancient Greek hoplites, including their armor, at https://www.larp.com/hoplite/index.html.

- This: http://www.steamfantasy.it/blog/2008/02/23/le-armature-una-panoramica-degli-acciai/ Italian website has good numbers on hardness and penetration tests.

- Alan Williams has done a thorough study of ancient and medieval armor: "The Knight and the Blast Furnace", ISBN: 90 04 12498 5.